- Home

- Stieg Larsson

Millennium 03 - The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest Page 15

Millennium 03 - The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest Read online

Page 15

Sandberg glanced at Wadensjöö.

“Evert … you have to understand that … we don’t do things like that any more,” Wadensjöö said. “It’s a new era. We deal more with computer hacking and electronic surveillance and such like. We don’t have the resources for what you’d think of as an operations unit.”

Gullberg leaned forward. “Wadensjöö, you’re going to have to sort out some resources pretty damn fast. Hire some people. Hire a bunch of skinheads from the Yugo mafia who can whack Blomkvist over the head if necessary. But those two copies have to be recovered. If they don’t have the copies, they don’t have the evidence. If you can’t manage a simple job like that then you might as well sit here with your thumb up your backside until the constitutional committee comes knocking on your door.”

Gullberg and Wadensjöö glared at each other for a long moment.

“I can handle it,” Sandberg said suddenly.

“Are you sure?”

Sandberg nodded.

“Good. Starting now, Clinton is your boss. He’s the one you take your orders from.”

Sandberg nodded his agreement.

“It’s going to involve a lot of surveillance,” Nyström said. “I can suggest a few names. We have a man in the external organization, Mårtensson – he works as a bodyguard in S.I.S. He’s fearless and shows promise. I’ve been considering bringing him in here. I’ve even thought that he could take my place one day.”

“That sounds good,” Gullberg said. “Clinton can decide.”

“I’m afraid there might be a third copy,” Nyström said.

“Where?”

“This afternoon I found out that Salander has taken on a lawyer. Her name is Annika Giannini. She’s Blomkvist’s sister.”

Gullberg pondered this news. “You’re right. Blomkvist will have given his sister a copy. He must have. In other words, we have to keep tabs on all three of them – Berger, Blomkvist and Giannini – until further notice.”

“I don’t think we have to worry about Berger. There was a report today that she’s going to be the new editor-in-chief at Svenska Morgon-Posten. She’s finished with Millennium.”

“Check her out anyway. As far as Millennium is concerned, we’re going to need telephone taps and bugs in everyone’s homes, and at the offices. We have to check their email. We have to know who they meet and who they talk to. And we would very much like to know what strategy they’re planning. Above all we have to get those copies of the report. A whole lot of stuff, in other words.”

Wadensjöö sounded doubtful. “Evert, you’re asking us to run an operation against an influential magazine and the editor-in-chief of S.M.P. That’s just about the riskiest thing we could do.”

“Understand this: you have no choice. Either you roll up your sleeves or it’s time for somebody else to take over here.”

The challenge hung like a cloud over the table.

“I think I can handle Millennium,” Sandberg said at last. “But none of this solves the basic problem. What do we do with Zalachenko? If he talks, anything else we pull off is useless.”

“I know. That’s my part of the operation,” Gullberg said. “I think I have an argument that will persuade Zalachenko to keep his mouth shut. But it’s going to take some preparation. I’m leaving for Göteborg later this afternoon.”

He paused and looked around the room. Then he fixed his eyes on Wadensjöö.

“Clinton will make the operational decisions while I’m gone,” he said.

Not until Monday evening did Dr Endrin decide, in consultation with her colleague Dr Jonasson, that Salander’s condition was stable enough for her to have visitors. First, two police inspectors were given fifteen minutes to ask her questions. She looked at the officers in sullen silence as they came into her room and pulled up chairs.

“Hello. My name is Marcus Erlander, Criminal Inspector. I work in the Violent Crimes Division here in Göteborg. This is my colleague Inspector Modig from the Stockholm police.”

Salander said nothing. Her expression did not change. She recognized Modig as one of the officers in Bublanski’s team. Erlander gave her a cool smile.

“I’ve been told that you don’t generally communicate much with the authorities. Let me put it on record that you do not have to say anything at all. But I would be grateful if you would listen to what we have to say. We have a number of things to discuss with you, but we don’t have time to go into them all today. There’ll be opportunities later.”

Salander still said nothing.

“First of all, I’d like to let you know that your friend Mikael Blomkvist has told us that a lawyer by the name of Annika Giannini is willing to represent you, and that she knows about the case. He says that he already mentioned her name to you in connection with something else. I need you to confirm that this would be your intention. I’d also like to know if you want Giannini to come here to Göteborg, the better to represent you.”

Annika Giannini. Blomkvist’s sister. He had mentioned her in an email. Salander had not thought about the fact that she would need a lawyer.

“I’m sorry, but I have to insist that you answer the question. A yes or no will be fine. If you say yes, the prosecutor here in Göteborg will contact Advokat Giannini. If you say no, the court will appoint a defence lawyer on your behalf. Which do you prefer?”

Salander considered the choice. She assumed that she really would need a lawyer, but having Kalle Bastard Blomkvist’s sister working for her was hard to stomach. On the other hand, some unknown lawyer appointed by the court would probably be worse. She rasped out a single word:

“Giannini.”

“Good. Thank you. Now I have a question for you. You don’t have to say anything before your lawyer gets here, but this question does not, as far as I can see, affect you or your welfare. The police are looking for a German citizen by the name of Ronald Niedermann, wanted for the murder of a policeman.”

Salander frowned. She had no clue as to what had happened after she had swung the axe at Zalachenko’s head.

“As far as the Göteborg police are concerned, they are anxious to arrest him as soon as possible. My colleague here would like to question him also in connection with the three recent murders in Stockholm. You should know that you are no longer a suspect in those cases. So we are asking for your help. Do you have any idea … can you give us any help at all in finding this man?”

Salander flicked her eyes suspiciously from Erlander to Modig and back.

They don’t know that he’s my brother.

Then she considered whether she wanted Niedermann caught or not. Most of all she wanted to take him to a hole in the ground in Gosseberga and bury him. Finally she shrugged. Which she should not have done, because pain flew through her left shoulder.

“What day is it today?” she said.

“Monday.”

She thought about that. “The first time I heard the name Ronald Niedermann was last Thursday. I tracked him to Gosseberga. I have no idea where he is or where he might go, but he’ll try to get out of the country as soon as he can.”

“Why would he flee abroad?”

Salander thought about it. “Because while Niedermann was out digging a grave for me, Zalachenko told me that things were getting too hot and that it had already been decided that Niedermann should leave the country for a while.”

Salander had not exchanged this many words with a police officer since she was twelve.

“Zalachenko … so that’s your father?”

Well, at least they had worked that one out. Probably thanks to Kalle Bastard Blomkvist.

“I have to tell you that your father has made a formal accusation to the police stating that you tried to murder him. The case is now at the prosecutor’s office, and he has to decide whether to bring charges. But you have already been placed under arrest on a charge of grievous bodily harm, for having struck Zalachenko on the head with an axe.”

There was a long silence. Then Modig leaned forwa

rd and said in a low voice, “I just want to say that we on the police force don’t put much faith in Zalachenko’s story. Do have a serious discussion with your lawyer so we can come back later and have another talk.”

The detectives stood up.

“Thanks for the help with Niedermann,” Erlander said.

Salander was surprised that the officers had treated her in such a correct, almost friendly manner. She thought about what the Modig woman had said. There would be some ulterior motive, she decided.

CHAPTER 7

Monday, 11.iv – Tuesday, 12.iv

At 5.45 p.m. on Monday Blomkvist closed the lid on his iBook and got up from the kitchen table in his apartment on Bellmansgatan. He put on a jacket and walked to Milton Security’s offices at Slussen. He took the lift up to the reception on the fourth floor and was immediately shown into a conference room. It was 6.00 p.m. on the dot, but he was the last to arrive.

“Hello, Dragan,” he said and shook hands. “Thank you for being willing to host this informal meeting.”

Blomkvist looked around the room. There were four others there: his sister, Salander’s former guardian Holger Palmgren, Malin Eriksson, and former Criminal Inspector Sonny Bohman, who now worked for Milton Security. At Armansky’s instruction Bohman had been following the Salander investigation from the very start.

Palmgren was on his first outing in more than two years. Dr Sivarnandan of the Ersta rehabilitation home had been less than enchanted at the idea of letting him out, but Palmgren himself had insisted. He had come by special transport for the disabled, accompanied by his personal nurse, Johanna Karolina Oskarsson, whose salary was paid from a fund that had been mysteriously established to provide Palmgren with the best possible care. The nurse was sitting in an office next to the conference room. She had brought a book with her. Blomkvist closed the door behind him.

“For those of you who haven’t met her before, this is Malin Eriksson, Millennium’s editor-in-chief. I asked her to be here because what we’re going to discuss will also affect her job.”

“O.K.,” Armansky said. “Everyone’s here. I’m all ears.”

Blomkvist stood at Armansky’s whiteboard and picked up a marker. He looked around.

“This is probably the craziest thing I’ve ever been involved with,” he said. “When this is all over I’m going to found an association called ‘The Knights of the Idiotic Table’ and its purpose will be to arrange an annual dinner where we tell stories about Lisbeth Salander. You’re all members.”

He paused.

“So, this is how things really are,” he said, and he began to make a list of headings on Armansky’s whiteboard. He talked for a good thirty minutes. Afterwards the discussion went on for almost three hours.

Gullberg sat down next to Clinton when their meeting was over. They spoke in low voices for a few minutes before Gullberg stood up. The old comrades shook hands.

Gullberg took a taxi to Frey’s, packed his briefcase and checked out. He took the late afternoon train to Göteborg. He chose first class and had the compartment to himself. When he passed Årstabron he took out a ballpoint pen and a plain paper pad. He thought for a long while and then began to write. He filled half the page before he stopped and tore the sheet off the pad.

Forged documents had never been his department or his expertise, but here the task was simplified by the fact that the letters he was writing would be signed by himself. What complicated the issue was that not a word of what he was writing was true.

By the time the train went through Nyköping he had already discarded a number of drafts, but he was starting to get a line on how the letters should be expressed. When they arrived in Göteborg he had twelve letters he was satisfied with. He made sure he had left clear fingerprints on each sheet.

At Göteborg Central Station he tracked down a photocopier and made copies of the letters. Then he bought envelopes and stamps and posted the letters in a box with a 9.00 p.m. collection.

Gullberg took a taxi to City Hotel on Lorensbergsgatan, where Clinton had already booked a room for him. It was the same hotel Blomkvist had spent the night in several days before. He went straight to his room and sat on the bed. He was completely exhausted and realized that he had eaten only two slices of bread all day. Yet he was not hungry. He undressed, stretched out in bed, and almost at once fell asleep.

Salander woke with a start when she heard the door open. She knew right away that it was not one of the night nurses. She opened her eyes to two narrow slits and saw a silhouette with crutches in the doorway. Zalachenko was watching her in the light that came from the corridor.

Without moving her head she glanced at the digital clock: 3.10 a.m.

She then glanced at the bedside table and saw the water glass. She calculated the distance. She could just reach it without having to move her body.

It would take a very few seconds to stretch out her arm and break off the rim of the glass with a firm rap against the hard edge of the table. It would take half a second to shove the broken edge into Zalachenko’s throat if he leaned over her. She looked for other options, but the glass was her only reachable weapon.

She relaxed and waited.

Zalachenko stood in the doorway for two minutes without moving. Then gingerly he closed the door.

She heard the faint scraping of the crutches as he quietly retreated down the corridor.

Five minutes later she propped herself up on her right elbow, reached for the glass, and took a long drink of water. She swung her legs over the edge of the bed and pulled the electrodes off her arms and chest. With an effort she stood up and swayed unsteadily. It took her about a minute to gain control over her body. She hobbled to the door and leaned against the wall to catch her breath. She was in a cold sweat. Then she turned icy with rage.

Fuck you, Zalachenko. Let’s end this right here and now.

She needed a weapon.

The next moment she heard quick heels clacking in the corridor.

Shit. The electrodes.

“What in God’s name are you doing up?” the night nurse said.

“I had to … go … to the toilet,” Salander said breathlessly.

“Get back into bed at once.”

She took Salander’s hand and helped her into the bed. Then she got a bedpan.

“When you have to go to the toilet, just ring for us. That’s what this button is for.”

Blomkvist woke up at 10.30 on Tuesday, showered, put on coffee, and then sat down with his iBook. After the meeting at Milton Security the previous evening, he had come home and worked until 5.00 a.m. The story was beginning at last to take shape. Zalachenko’s biography was still vague – all he had was what he had blackmailed Björck to reveal, as well as the handful of details Palmgren had been able to provide. Salander’s story was pretty much done. He explained step by step how she had been targeted by a gang of Cold-Warmongers at S.I.S. and locked away in a psychiatric hospital to stop her blowing the gaff on Zalachenko.

He was pleased with what he had written. There were still some holes that he would have to fill, but he knew that he had one hell of a story. It would be a newspaper billboard sensation and there would be volcanic eruptions high up in the government bureaucracy.

He smoked a cigarette while he thought.

He could see two particular gaps that needed attention. One was manageable. He had to deal with Teleborian, and he was looking forward to that assignment. When he was finished with him, the renowned children’s psychiatrist would be one of the most detested men in Sweden. That was one thing.

The second thing was more complicated.

The men who conspired against Salander – he thought of them as the Zalachenko club – were inside the Security Police. He knew one, Gunnar Björck, but Björck could not possibly be the only man responsible. There had to be a group … a division or unit of some sort. There must be chiefs, operations managers. There had to be a budget. But he had no idea how to go about identifying these people, wher

e even to start. He had only the vaguest notion of how Säpo was organized.

On Monday he had begun his research by sending Cortez to the second-hand bookshops on Södermalm, to buy every book which in any way dealt with the Security Police. Cortez had come to his apartment in the afternoon with six books.

Espionage in Sweden by Mikael Rosquist (Tempus, 1988); Säpo Chief 1962–1970 by P.G. Vinge (Wahlström & Widstrand, 1988); Secret Forces by Jan Ottosson and Lars Magnusson (Tiden, 1991); Power Struggle for Säpo by Erik Magnusson (Corona, 1989); An Assignment by Carl Lidbom (Wahlström & Widstrand, 1990); and – somewhat surprisingly – An Agent in Place by Thomas Whiteside (Ballantine, 1966), which dealt with the Wennerström affair. The Wennerström affair of the ’60s, not Blomkvist’s own much more recent Wennerström affair.

He had spent much of Monday night and the early hours of Tuesday morning reading or at least skimming the books. When he had finished he made some observations. First, most of the books published about the Security Police were from the late ’80s. An Internet search showed that there was hardly any current literature on the subject.

Second, there did not seem to be any intelligible basic overview of the activities of the Swedish secret police over the years. This may have been because many documents were stamped Top Secret and were therefore off limits, but there did not seem to be any single institution, researcher or media that had carried out a critical examination of Säpo.

He also noticed another odd thing: there was no bibliography in any one of the books Cortez had found. On the other hand, the footnotes often referred to articles in the evening newspapers, or to interviews with some old, retired Säpo hand.

The book Secret Forces was fascinating but largely dealt with the time before and during the Second World War. Blomkvist regarded P.G. Vinge’s memoir as propaganda, written in self-defence by a severely criticized Säpo chief who was eventually fired. An Agent in Place contained so much inaccurate information about Sweden in the first chapter that he threw the book into the wastepaper basket. The only two books with any real ambition to portray the work of the Security Police were Power Struggle for Säpo and Espionage in Sweden. They contained data, names and organizational charts. He found Magnusson’s book to be especially worthwhile reading. Even though it did not offer any answers to his immediate questions, it provided a good account of Säpo as a structure as well as its primary concerns over several decades.

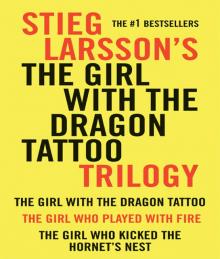

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest

The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest The Girl Who Played with Fire

The Girl Who Played with Fire The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo m(-1

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo m(-1 The Girl who played with Fire m(-2

The Girl who played with Fire m(-2 Millennium 01 - The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

Millennium 01 - The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo The Girl Who Kicked The Hornets’ Nest m(-3

The Girl Who Kicked The Hornets’ Nest m(-3 Millennium 02 - The Girl Who Played with Fire

Millennium 02 - The Girl Who Played with Fire Millennium 03 - The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest

Millennium 03 - The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo Trilogy Bundle

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo Trilogy Bundle![Millenium [02] The Girl Who Played With Fire Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/millenium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_preview.jpg) Millenium [02] The Girl Who Played With Fire

Millenium [02] The Girl Who Played With Fire