- Home

- Stieg Larsson

Millennium 03 - The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest Page 17

Millennium 03 - The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest Read online

Page 17

That had not been part of the plan anyway. Clinton would take care of Giannini. Gullberg’s only job was Zalachenko.

He looked around the corridor and saw that he was being watched by nurses, patients and visitors. He raised the pistol and fired at a picture hanging on the wall at the end of the corridor. His spectators vanished as if by magic.

He glanced one last time at the door to Salander’s room. Then he walked decisively back to Zalachenko’s room and closed the door. He sat in the visitor’s chair and looked at the Russian defector who had been such an intimate part of his own life for so many years.

He sat still for almost ten minutes before he heard movement in the corridor and was aware that the police had arrived. By now he was not thinking of anything in particular.

Then he raised the revolver one last time, held it to his temple, and squeezed the trigger.

As the situation developed, the futility of attempting suicide in the middle of a hospital became apparent. Gullberg was transported at top speed to the hospital’s trauma unit, where Dr Jonasson received him and immediately initiated a battery of measures to maintain his vital functions.

For the second time in less than a week Jonasson performed emergency surgery, extracting a full-metal-jacketed bullet from human brain tissue. After a five-hour operation, Gullberg’s condition was critical. But he was still alive.

Yet Gullberg’s injuries were considerably more serious than those that Salander had sustained. He hovered between life and death for several days.

Blomkvist was at the Kaffebar on Hornsgatan when he heard on the radio that a 66-year-old unnamed man, suspected of attempting to murder the fugitive Lisbeth Salander, had been shot and killed at Sahlgrenska hospital in Göteborg. He left his coffee untouched, picked up his laptop case, and hurried off towards the editorial offices on Götgatan. He had crossed Mariatorget and was just turning up St Paulsgatan when his mobile beeped. He answered on the run.

“Blomkvist.”

“Hi, it’s Malin.”

“I heard the news. Do we know who the killer was?”

“Not yet. Henry is chasing it down.”

“I’m on the way in. Be there in five minutes.”

Blomkvist ran into Cortez at the entrance to the Millennium offices.

“Ekström’s holding a press conference at 3.00,” Cortez said. “I’m going to Kungsholmen now.”

“What do we know?” Blomkvist shouted after him.

“Ask Malin,” Cortez said, and was gone.

Blomkvist headed into Berger’s … wrong, Eriksson’s office. She was on the telephone and writing furiously on a yellow Post-it. She waved him away. Blomkvist went into the kitchenette and poured coffee with milk into two mugs marked with the logos of the K.D.U. and S.S.U. political parties. When he returned she had just finished her call. He gave her the S.S.U. mug.

“Right,” she said. “Zalachenko was shot dead at 1.15.” She looked at Blomkvist. “I just spoke to a nurse at Sahlgrenska. She says that the murderer was a man in his seventies, who arrived with flowers for Zalachenko minutes before the murder. He shot Zalachenko in the head several times and then shot himself. Zalachenko is dead. The murderer is just about alive and in surgery.”

Blomkvist breathed more easily. Ever since he had heard the news at the Kaffebar he had had his heart in his throat and a panicky feeling that Salander might have been the killer. That really would have thrown a spanner in the works.

“Do we have the name of the assailant?”

Eriksson shook her head as the telephone rang again. She took the call, and from the conversation Blomkvist gathered that it was a stringer in Göteborg whom Eriksson had sent to Sahlgrenska. He went to his own office and sat down.

It felt as if it was the first time in weeks that he had even been to his office. There was a pile of unopened post that he shoved firmly to one side. He called his sister.

“Giannini.”

“It’s Mikael. Did you hear what happened at Sahlgrenska?”

“You could say so.”

“Where are you?”

“At the hospital. That bastard aimed at me, too.”

Blomkvist sat speechless for several seconds before he fully took in what his sister had said.

“What on earth… you were there?”

“Yes. It was the most horrendous thing I’ve ever experienced.”

“Are you hurt?”

“No. But he tried to get into Lisbeth’s room. I blockaded the door and locked us in the bathroom.”

Blomkvist’s whole world suddenly felt off balance. His sister had almost…

“How is she?” he said.

“She’s not hurt. Or, I mean, she wasn’t hurt in today’s drama at least.”

He let that sink in.

“Annika, do you know anything at all about the murderer?”

“Not a thing. He was an older man, neatly dressed. I thought he looked rather bewildered. I’ve never seen him before, but I came up in the lift with him a few minutes before it all happened.”

“And Zalachenko is dead, no question?”

“Yes. I heard three shots, and according to what I’ve overheard he was shot in the head all three times. But it’s been utter chaos here, with a thousand policemen, and they’re evacuating a ward for acutely ill and injured patients who really ought not to be moved. When the police arrived one of them tried to question Lisbeth before they even bothered to ask what shape she’s in. I had to read them the riot act.”

Inspector Erlander saw Giannini through the doorway to Salander’s room. The lawyer had her mobile pressed to her ear, so he waited for her to finish her call.

Two hours after the murder there was still chaos in the corridor. Zalachenko’s room was sealed off. Doctors had tried resuscitation immediately after the shooting, but soon gave up. He was beyond all help. His body was sent to the pathologist, and the crime scene investigation proceeded as best it could under the circumstances.

Erlander’s mobile chimed. It was Fredrik Malmberg from the investigative team.

“We’ve got a positive I.D. on the murderer,” Malmberg said. “His name is Evert Gullberg and he’s seventy-eight years old.”

Seventy-eight. Quite elderly for a murderer.

“And who the hell is Evert Gullberg?”

“Retired. Lives in Laholm. Apparently he was a tax lawyer. I got a call from S.I.S. who told me that they had recently initiated a preliminary investigation against him.”

“When and why?”

“I don’t know when. But apparently he had a habit of sending crazy and threatening letters to people in government.”

“Such as who?”

“The Minister of Justice, for one.”

Erlander sighed. So, a madman. A fanatic.

“This morning Säpo got calls from several newspapers who had received letters from Gullberg. The Ministry of Justice also called, because Gullberg had made specific death threats against Karl Axel Bodin.”

“I want copies of the letters.”

“From Säpo?”

“Yes, damn it. Drive up to Stockholm and pick them up in person if necessary. I want them on my desk when I get back to H.Q. Which will be in about an hour.”

He thought for a second and then asked one more question.

“Was it Säpo that called you?”

“That’s what I told you.”

“I mean … they called you, not vice versa?”

“Exactly.”

Erlander closed his mobile.

He wondered what had got into Säpo to make them, out of the blue, feel the need to get in touch with the police – of their own accord. Ordinarily you couldn’t get a word out of them.

Wadensjöö flung open the door to the room at the Section where Clinton was resting. Clinton sat up cautiously.

“Just what the bloody hell is going on?” Wadensjöö shrieked. “Gullberg has murdered Zalachenko and then shot himself in the head.”

“I know,” Clinton said.

“You know?” Wadensjöö yelled. He was bright red in the face and looked as if he was about to have a stroke. “He shot himself, for Christ’s sake. He tried to commit suicide. Is he out of his mind?”

“You mean he’s alive?”

“For the time being, yes, but he has massive brain damage.”

Clinton sighed. “Such a shame,” he said with real sorrow in his voice.

“Shame?” Wadensjöö burst out. “Gullberg is out of his mind. Don’t you understand what—”

Clinton cut him off.

“Gullberg has cancer of the stomach, colon and bladder. He’s been dying for several months, and in the best case he had only a few months left.”

“Cancer?”

“He’s been carrying that gun around for the past six months, determined to use it as soon as the pain became unbearable and before the disease turned him into a vegetable. But he was able to do one last favour for the Section. He went out in grand style.”

Wadensjöö was almost beside himself. “You knew? You knew that he was thinking of killing Zalachenko?”

“Naturally. His assignment was to make sure that Zalachenko never got a chance to talk. And as you know, you couldn’t threaten or reason with that man.”

“But don’t you understand what a scandal this could turn into? Are you just as barmy as Gullberg?”

Clinton got to his feet laboriously. He looked Wadensjöö in the eye and handed him a stack of fax copies.

“It was an operational decision. I mourn for my friend, but I’ll probably be following him pretty soon. As far as a scandal goes … A retired tax lawyer wrote paranoid letters to newspapers, the police, and the Ministry of Justice. Here’s a sample of them. Gullberg blames Zalachenko for everything from the Palme assassination to trying to poison the Swedish people with chlorine. The letters are plainly the work of a lunatic and were illegible in places, with capital letters, underlining, and exclamation marks. I especially like the way he wrote in the margin.”

Wadensjöö read the letters with rising astonishment. He put a hand to his brow.

Clinton said: “Whatever happens, Zalachenko’s death will have nothing to do with the Section. It was just some demented pensioner who fired the shots.” He paused. “The important thing is that, starting from now, you have to get on board with the program. And don’t rock the boat.” He fixed his gaze on Wadensjöö. There was steel in the sick man’s eyes. “What you have to understand is that the Section functions as the spear head for the total defence of the nation. We’re Sweden’s last line of defence. Our job is to watch over the security of our country. Everything else is unimportant.”

Wadensjöö regarded Clinton with doubt in his eyes.

“We’re the ones who don’t exist,” Clinton went on. “We’re the ones nobody will ever thank. We’re the ones who have to make the decisions that nobody else wants to make. Least of all the politicians.” His voice quivered with contempt as he spoke those last words. “Do as I say and the Section might survive. For that to happen, we have to be decisive and resort to tough measures.”

Wadensjöö felt the panic rise.

Cortez wrote feverishly, trying to get down every word that was said from the podium at the police press office at Kungsholmen. Prosecutor Ekström had begun. He explained that it had been decided that the investigation into the police killing in Gosseberga – for which Ronald Niedermann was being sought – would be placed under the jurisdiction of a prosecutor in Göteborg. The rest of the investigation concerning Niedermann would be handled by Ekström himself. Niedermann was a suspect in the murders of Dag Svensson and Mia Johansson. No mention was made of Advokat Bjurman. Ekström had also to investigate and bring charges against Lisbeth Salander, who was under suspicion for a long list of crimes.

He explained that he had decided to go public with the information in the light of events that had occurred in Göteborg that day, including the fact that Salander’s father, Karl Axel Bodin, had been shot dead. The immediate reason for calling the press conference was that he wanted to deny the rumours already being circulated in the media. He had himself received a number of calls concerning these rumours.

“Based on current information, I am able to tell you that Karl Axel Bodin’s daughter, who is being held for the attempted murder of her father, had nothing to do with this morning’s events.”

“Then who was the murderer?” a reporter from Dagens Eko shouted.

“The man who at 1.15 today fired the fatal shots at Karl Axel Bodin before attempting to commit suicide has now been identified. He is a 78-year-old man who has been undergoing treatment for a terminal illness and the psychiatric problems associated with it.”

“Does he have any connection to Lisbeth Salander?”

“No. The man is a tragic figure who evidently acted alone, in accordance with his own paranoid delusions. The Security Police recently initiated an investigation of this man because he had written a number of apparently unstable letters to well-known politicians and the media. As recently as this morning, newspaper and government offices received letters in which he threatened to kill Karl Axel Bodin.”

“Why didn’t the police give Bodin protection?”

“The letters naming Bodin were sent only last night and thus arrived at the same time as the murder was being committed. There was no time to act.”

“What’s the killer’s name?”

“We will not give out that information until his next of kin have been notified.”

“What sort of background does he have?”

“As far as I understand, he previously worked as an accountant and tax lawyer. He has been retired for fifteen years. The investigation is still under way, but as you can appreciate from the letters he sent, it is a tragedy that could have been prevented if there had been more support within society.”

“Did he threaten anyone else?”

“I have been advised that he did, yes, but I do not have any details to pass on to you.”

“What will this mean for the case against Salander?”

“For the moment, nothing. We have Karl Axel Bodin’s own testimony from the officers who interviewed him, and we have extensive forensic evidence against her.”

“What about the reports that Bodin tried to murder his daughter?”

“That is under investigation, but there are strong indications that he did indeed attempt to kill her. As far as we can determine at the moment, it was a case of deep antagonism in a tragically dysfunctional family.”

Cortez scratched his ear. He noticed that the other reporters were taking notes as feverishly as he was.

Gunnar Björck felt an almost unquenchable panic when he heard the news about the shooting at Sahlgrenska hospital. He had terrible pain in his back.

It took him an hour to make up his mind. Then he picked up the telephone and tried to call his old protector in Laholm. There was no answer.

He listened to the news and heard a summary of what had been said at the press conference. Zalachenko had been shot by a 78-year-old tax specialist.

Good Lord, seventy-eight years old.

He tried again to call Gullberg, but again in vain.

Finally his uneasiness took the upper hand. He could not stay in the borrowed summer cabin in Smådalarö. He felt vulnerable and exposed. He needed time and space to think. He packed clothes, painkillers, and his wash bag. He did not want to use his own telephone, so he limped to the telephone booth at the grocer’s to call Landsort and book himself a room in the old ships’ pilot lookout. Landsort was the end of the world, and few people would look for him there. He booked the room for two weeks.

He glanced at his watch. He would have to hurry to make the last ferry. He went back to the cabin as fast as his aching back would permit. He made straight for the kitchen and checked that the coffee machine was turned off. Then he went to the hall to get his bag. He happened to look into the living room and stopped short in surprise.

At first he could not g

rasp what he was seeing.

In some mysterious way the ceiling lamp had been taken down and placed on the coffee table. In its place hung a rope from a hook, right above a stool that was usually in the kitchen.

Björck looked at the noose, failing to understand.

Then he heard movement behind him and felt his knees buckle.

Slowly he turned to look.

Two men stood there. They were southern European, by the look of them. He had no will to react when calmly they took him in a firm grip under both arms, lifted him off the ground, and carried him to the stool. When he tried to resist, pain shot like a knife through his back. He was almost paralysed as he felt himself being lifted on to the stool.

Sandberg was accompanied by a man who went by the nickname of Falun and who in his youth had been a professional burglar. He had, in time, retrained as a locksmith. Hans von Rottinger had first hired Falun for the Section in 1986 for an operation that involved forcing entry into the home of the leader of an anarchist group. After that, Falun had been hired from time to time until the mid-’90s, when there was less demand for this type of operation. Early that morning Clinton had revived the contact and given Falun an assignment. Falun would make 10,000 kronor tax-free for a job that would take about ten minutes. In return he had pledged not to steal anything from the apartment that was the target of the operation. The Section was not a criminal enterprise, after all.

Falun did not know exactly what interests Clinton represented, but he assumed it had something to do with the military. He had read Jan Guillou’s books, and he did not ask any questions. But it felt good to be back in the saddle again after so many years of silence from his former employer.

His job was to open the door. He was expert at breaking and entering. Even so, it still took five minutes to force the lock to Blomkvist’s apartment. Then Falun waited on the landing as Sandberg went in.

“I’m in,” Sandberg said into a handsfree mobile.

“Good,” Clinton said into his earpiece. “Take your time. Tell me what you see.”

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest

The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest The Girl Who Played with Fire

The Girl Who Played with Fire The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo m(-1

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo m(-1 The Girl who played with Fire m(-2

The Girl who played with Fire m(-2 Millennium 01 - The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

Millennium 01 - The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo The Girl Who Kicked The Hornets’ Nest m(-3

The Girl Who Kicked The Hornets’ Nest m(-3 Millennium 02 - The Girl Who Played with Fire

Millennium 02 - The Girl Who Played with Fire Millennium 03 - The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest

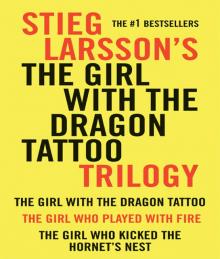

Millennium 03 - The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo Trilogy Bundle

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo Trilogy Bundle![Millenium [02] The Girl Who Played With Fire Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/millenium_02_the_girl_who_played_with_fire_preview.jpg) Millenium [02] The Girl Who Played With Fire

Millenium [02] The Girl Who Played With Fire